Semiconductor Integrated optics book published

The second edition of my book “Semiconductor Integrated Optics for Switching Light” has just been published (May 2021). Check out:-https://iopscience.iop.org/book/978-0-7503-3519-5 It’s a book on using semiconductor optical waveguides for controlling light. It provides a concise description of the physics and engineering of semiconductor optical waveguides for photonic and electronic switching with a focus on optical communication applications. It provides Python notebooks that illustrate the concepts discussed in the book. The book includes the following topics: linear and nonlinear optics, linear electro-optic effect electroabsorption and electrorefraction, nonlinear refraction, nonlinear optical devices.

There is supporting material in the form of a youtube video

There are are Python and Mathematica notebooks that can be used to help with the design of some of the devices discussed in the book.

Python notebooks at :-https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4506293

Mathematica notebooks:-https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4448672

Enjoy!

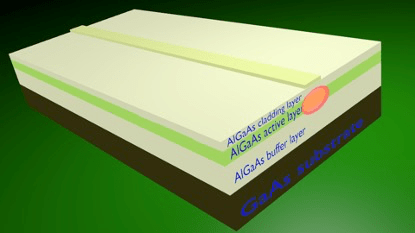

thick Al0.25Ga0.75As. The active layer is thick Al0.18Ga0.82As. The cladding layer is thick Al0.25Ga0.75As. The mesa strip is wide and in height. The approximate position of the guided light at the facet is indicated by the red area.

Why Your Computer Isn’t Getting Faster—And How Photonics Could Break the Deadlock

Introduction: The Speed We Can’t Use

For decades, we took for granted that computers would get exponentially faster every year. But if you’ve bought a new computer recently, you might have noticed something strange: the raw clock speed of its processor probably isn’t much faster than the one you had a decade ago. Since around 2004, the core clock speed of microprocessors has been largely stuck in the 3–5 GHz range. We’ve added more cores and clever software tricks, but the fundamental clock frequency of the processor has hit a wall.

The surprising reason for this stagnation isn’t that we can’t make transistors switch faster. The real culprit is thermodynamics. The dominant technology in computing, known as CMOS, has a primary weakness in heat management. Every time a transistor switches to process a ‘1’ or a ‘0’, it generates a tiny puff of heat. At billions of operations per second, those puffs add up to a thermal inferno that we simply can’t cool down fast enough. We’ve reached the physical limit of how much heat we can remove from a chip.

To break this deadlock, researchers are exploring a radical solution: getting rid of the electrons and switching with light itself. This field, known as all-optical switching, uses photons to process information. By using light to control light, it may be possible to bypass the thermal bottleneck that has plagued electronics for years, unlocking a new era of computational speed.

——————————————————————————–

1. The Real Enemy of Speed Is Heat, Not Time

The fundamental limit of modern computing is a law of physics. The second law of thermodynamics states that every switching operation increases entropy, or disorder. In the electronic world of CMOS chips, this increase in entropy inevitably ends up as waste heat. We’ve become so efficient at packing transistors onto silicon that we’ve reached a point where the heat generated can’t be dissipated quickly enough, limiting how fast we can run the chip.

The core problem is elegantly stated in research on the topic:

If CMOS does have any weakness it may be in the heat management associated with ultrafast switching.

The issue is not just the total amount of heat, but the physical speed limit at which a material can shed it. The industry is stuck with the thermal diffusion coefficient of silicon, a fundamental property that dictates how quickly heat can move through the material. This creates a hard physical ceiling on processing speed.

All-optical switching offers a clever way around this problem. In certain forms of optical computing, the entropy “price” for a switching operation is still paid, but it “does not end-up in heat.” Instead of heating the material, the cost of the operation is paid in more subtle ways—for instance, as the physics of these interactions shows, it can manifest as an increase in the phase uncertainty of the light itself.

This reframes the entire challenge of high-speed computing. The problem isn’t just about achieving raw speed; it’s about managing energy and heat. By shifting from electrons, which generate heat when they move, to photons, which can process information without thermal buildup, we open an entirely new path forward.

——————————————————————————–

2. You Can Steer a Beam of Light With Another Beam of Light

The central principle behind all-optical switching lies in a field called nonlinear optics. Normally, we think of materials like glass as having fixed optical properties—light passes through without changing the glass itself. However, at sufficiently high intensities, light can actually alter the optical properties of the material it’s traveling through.

One of the key mechanisms is the “optical Kerr effect,” where the intensity of a light beam changes the material’s refractive index (the property that determines how much the material bends light). A high-intensity pulse of light can essentially make a pathway temporarily more or less “optically dense” for other light passing through it.

Researchers use this principle to build devices like a “nonlinear directional coupler.” Think of two microscopic waveguides as two parallel lanes of a highway built from a special material. At low traffic volumes, cars (light pulses) naturally drift from the first lane into the second over a short distance. But a high-intensity “control” pulse is like a sudden, temporary change in the road surface of the first lane, making it ‘stickier’ and preventing any cars from drifting across. The control pulse creates a temporary barrier with light itself. In effect, the control beam of light acts as a switch, steering the data beam.

This all happens without any electronic-to-optical conversion, allowing for incredible speeds. Because the effect relies on the near-instantaneous response of bound electrons in the material, the ultimate switching speed limit is in the attosecond (a billionth of a billionth of a second) range. This is millions of times faster than the gigahertz clock speeds of today’s best processors, operating on a timescale where we can influence the very oscillation of a light wave itself.

——————————————————————————–

3. To Build the Perfect Switch, You Need the “Imperfect” Material

Building a practical all-optical switch presents a significant challenge. You need a material with a large nonlinear refractive index—the property that allows a control pulse to strongly affect a data pulse. At the same time, you must avoid a phenomenon called “two-photon absorption.” This is a process where the material absorbs two photons at once from the high-intensity control pulse, which wastes energy and, crucially, generates the very heat you’re trying to avoid.

The solution is a masterpiece of materials science. Using a semiconductor alloy called Aluminum Gallium Arsenide (AlxGa1−xAs), engineers can “tune” the material’s properties by precisely adjusting the aluminum fraction (the ‘x’). For the wavelengths used in optical communications (around 1550 nm), researchers discovered a “sweet spot.”

The ideal material isn’t a pure element but a precisely formulated alloy: Al₀.₁₈Ga₀.₈₂As. This specific composition adjusts the material’s electronic bandgap—the minimum energy required to excite an electron. The material is engineered so that the energy of a single photon is less than the bandgap, preventing it from being absorbed on its own. Crucially, the photon energy is also engineered to be less than half the bandgap energy. This makes it energetically impossible for two photons to combine their energy to excite an electron, thus eliminating two-photon absorption. This “just right” configuration maximizes the useful switching effect while minimizing wasteful, heat-generating absorption. It’s a powerful example of how quantum mechanics can be used to engineer a material with the exact compromise of properties needed to build a new technology.

——————————————————————————–

4. Running Absorption Backwards Could Create a New Kind of Laser

Physics often has a beautiful symmetry. The same process that can be an undesirable side effect can sometimes be flipped on its head to create a powerful new tool. The problem of “two-photon absorption” has an inverse: “two-photon gain.”

Under normal conditions, a material can absorb two photons at once. However, if you pump the material with external energy—similar to how a conventional laser works—you can create a “population inversion” (a state where more electrons are in a high-energy state than a low-energy one, making the material eager to release energy rather than absorb it). In this energized state, the process reverses. Instead of absorbing two photons, an incoming photon can stimulate the material to emit two highly correlated photons simultaneously.

This phenomenon could be the key to building a “two-photon semiconductor laser.” Such a device would be an entirely new kind of light source capable of producing the ultrashort, high-intensity pulses of highly correlated photons that are required for high-speed, all-optical processing. While a practical two-photon semiconductor laser has yet to be fully realized, the principle shows how even the physical limitations in one area can become the foundation for groundbreaking technology in another.

——————————————————————————–

Conclusion: A New Light for Computation

To continue advancing the speed of information processing, we may need to fundamentally shift our tools from electrons to photons. All-optical switching bypasses the thermal limits of today’s electronics by using light to control light, a process that can occur on timescales thousands of times faster than current processors without generating waste heat.

From the realization that heat, not time, is the true barrier, to the engineering of “imperfect” materials with perfectly balanced quantum properties, the path toward optical computing is illuminated by surprising and elegant physics. Even parasitic effects like two-photon absorption can be inverted to create new technologies like two-photon lasers.

While significant engineering challenges remain, the physics is clear. The question is no longer if we can build computers that run on light, but what new worlds will we discover when computation can happen on the timescale of a single light wave? The answer could redefine everything from artificial intelligence to drug discovery, opening up computational frontiers that today exist only in theory.